-

Posts

8,253 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

31

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Everything posted by Harlequinmania

-

Click through to see the images. The study (published this month in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.) concludes that corals that live in the same area and look exactly alike might not even be the same species. As many reefkeepers know, corals can often assume very different morphologies under different conditions. Under different conditions, two corals of the same species might look radically different. Under specific conditions, two corals of different species might look identical. Just as interesting is how their differences (invisible to the naked eye) may help one species succeed where another might fail. For example, the SPS corals Porites lobata and Porites evermanni exist at the same reef sites and look indistinguishable. However, when the scientists analyzed their data, they discovered not only two distinct species growing together but P.evermanni was more successful at reproducing than P.lobata. The reason: Under their copycat exteriors, P.evermanni were more hospitable to boring mussels growing in their skeleton. Triggers hunt these mussels, biting off chunks of the Porites and distributing the fragments over the reef thus creating new colonies from these frags. This is similar to how many terrestrial plants propagate. From Penn State University Marine biologists unmask species diversity in coral reefs Two corals (Porites sp.) growing side by side. The left colony is bleached: it appears white. During bleaching the partnership between symbiotic algae that live inside the coral cells and the coral host breaks down giving the coral a white appearance. The colony on the right is still green/brown and has a healthy population of symbionts living in its tissue. Image: Iliana Baums, Penn State UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Rising water temperatures due to climate change are putting coral reefs in jeopardy, but a surprising discovery by a team of marine biologists suggests that very similar looking coral species differ in how they survive in harsh environments. "We've found that previously unrecognized species diversity was hiding some corals' ability to respond to climate change," said Iliana Baums, associate professor of biology at Penn State. A scientific paper describing the team's discovery will be published in the print edition of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B on Feb. 7, 2014. Coral reefs protect shorelines from battering hurricanes and generate millions of dollars in recreation revenue each year. They also provide habitat for an abundance of seafood and serve as a discovery ground for new drugs and medicines. Baums led an international research team that included Jennifer Boulay, a Penn State graduate student; Jorge Cortes, professor at the University of Costa Rica; and Michael Hellberg, associate professor of biological sciences at Louisiana State University. The researchers sampled the lobe coral Porites lobata in the eastern Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Central America and genetically analyzed the samples to reveal differences among various sample locations. When the scientists analyzed their data, they found an unexpected pattern: one that suggested two separate lineages of coral that look deceivingly similar and sometimes live together in the same location. Genetic data confirmed that the samples were not all Porites lobata, as the researchers initially thought. Instead, some belonged to the species P. evermanni. "That surprised us," Baums said. "These two lineages look identical and we thought they were all the same coral species, but evermanni has a very different genetic makeup. We knew about P. evermanni -- it's not a new species -- but we didn't expect to find it in the Eastern Pacific, which is a suboptimal environment for coral. Typically you find P. evermanni in the waters of the Hawaiian Islands." Boulay wondered if the two species differed in the way they live. She found that P. evermanni was less susceptible to bleaching than P. lobata. Bleaching occurs when the symbiotic relationship that corals share with single-celled algae breaks down as a result of an increase in water temperature. "If water temperatures continue to rise, and they surely will, coral species that succumb to bleaching more easily will die," Baums said. "So we're going to see a shift in the relative abundance of these two species." Boulay found other important differences: P. evermanni had many genetically identical clones, which means that this species is reproducing asexually by breaking apart, although P. lobata did not. Further, the clonally reproducing P. evermanni, on average, housed many more tiny mussels that lived within the coral colonies' skeletons. The mussels poke through the surface of the colonies and form keyhole-shaped holes. The researchers then wanted to determine the connection between P. evermanni's ability to clonally reproduce and its interactions with the mussels and other members of the reef community in the eastern Pacific. Cortes remembered that several years ago a colleague had reported a finding that some corals are a target of biting triggerfish. "That was the missing piece," Baums said. "We realized that triggerfish were eating mussels inside the coral skeletons, and to get at the mussels the fish have to bite the coral. Then they spit the fragments out, and those fragments land on the ocean floor and grow into new colonies. "This is what's fascinating," Baums continued. "No one has ever realized how important fish might be in helping corals reproduce, and here we have evidence that triggerfish attacks on P. evermanni result in asexual reproduction -- the coral fragments cloning themselves. Conversely, the other coral lineage, Porites lobata, has fewer mussels and reproduces sexually through its larvae." The benefit of asexual reproduction, Baums explained, is that corals living in a harsh environment such as the Eastern Pacific might have a hard time finding partners for sexual reproduction. "It takes two to tango so you need a partner," she said. "In areas of the Eastern Pacific that are so harsh that only a few individuals can survive, it might be easier for the coral to clone itself, ensuring that the offspring can survive as well." As for the difference in bleaching, there are two possible explanations. One possibility is that the types of algae living in the coral species are different, and one of them can withstand a hotter temperature. "Just like in your garden -- the tomatoes like the heat more than the cauliflower does," said Baums. Another possibility is that the difference is not in the algae but in the corals themselves. "In the literature there's been a lot of attention paid to how different algal species react to increases in temperature and whether, if a coral species could switch to a hardier alga, it could survive hotter temperatures," Baums said. But what the researchers found suggested a different scenario. Even though the two coral species have the same algal species, bleaching still differs. That suggests it's the coral host that contributes to bleaching. "The good news in all of this is that some of these corals are true survivors, especially in the eastern Pacific," Baums said. "It's a rough place for coral to live but they are still hanging around. So if we can figure out how to slow down climate change and keep identifying some hardy corals, we can do something about preserving coral reefs." The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Grant #OCE-0550294. View the full article

-

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

And recent photo of the location after the start of reno . The wall should be hack off by end of this week. -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

Some photos of the area where the Tank build will be . Area before the start of reno. -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

Mine is nothing compare to his lol... -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

-

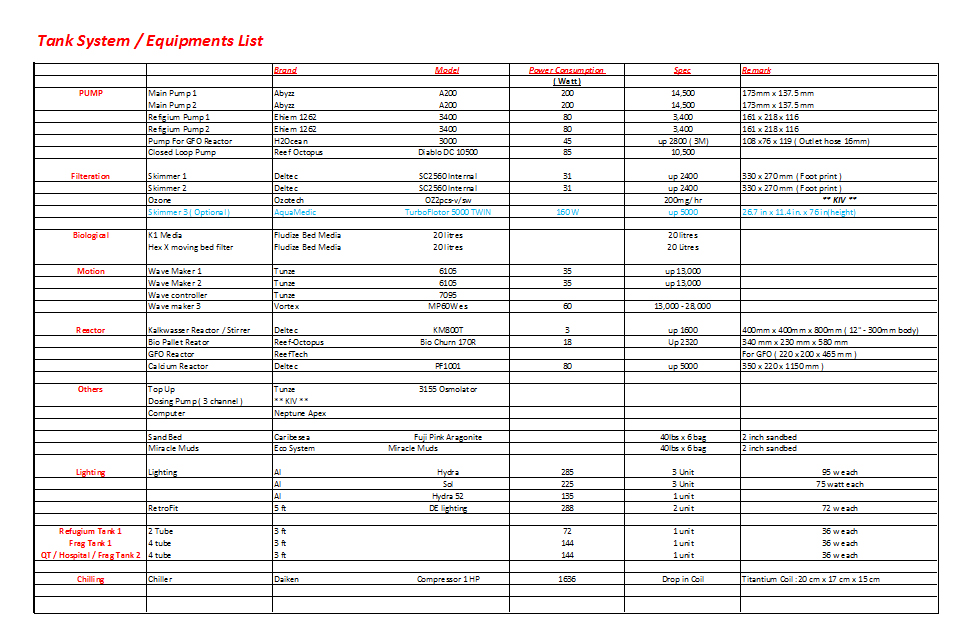

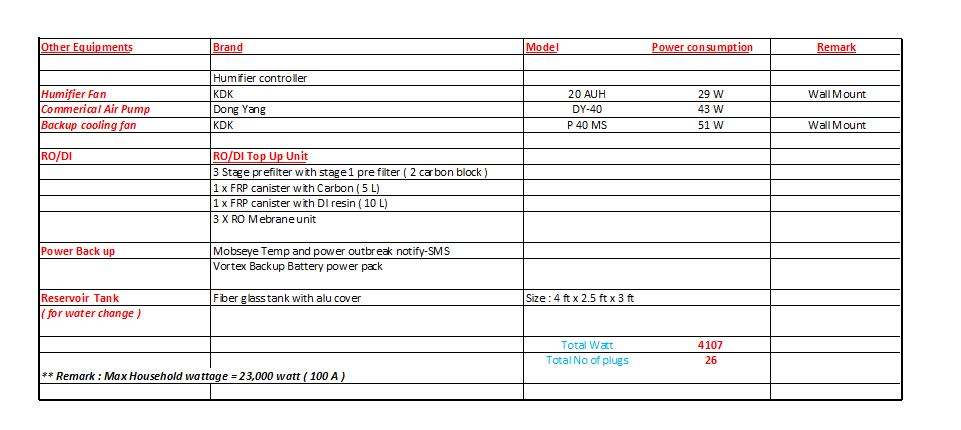

Starting this new thread to share the new tank build of my system. Idea / concept of setup After all the years in the hobby reefing from a small 2 ft tank, to a current 6ft tank in my home. It has always been a dream to have a beautiful large reef tank in my dream home surrounded by garden and natural. Luckily , I am able to fulfill this dream in the early stage of life with the support of my family and friends. The concept of having a dedicated Fish room is something many reef addicts like me always dream of, and the opportunity of turning this crazy idea into a reality strike when we got our new place. While searching around on the internet for some ideal, and inspiration of my new setup I came about this photo of a 3D wall mount aquarium and it strike me to have a similar concept on my new tank. So the story begin lol… Some specification of my new setup Main Tank : 72" X 48" x 30 " ( 6ft x 4ft x 2.5ft ) - Plexiglas Sump Tank : 62" x 36" x 24 " - PP Frag Tank 1 : 36" x 24" 18" - Glass - 12mm QT / Hospital Tank / Frag Tank :36" x 24" 18" - Glass 12 mm Refugium Tank :36" x 24" 18" - Glass 12mm Cryptic Tank : 36" x 24" 18" - Glass 12mm Frag sump tank 1: 36" x 24" 20" - Glass 12mm Frag sump tank 2 : 36" x 24" 20" - Glass 12mm Total Water volume : 4163.82 ( 1041 Gallon )

-

Click through to see the images. 10,000 pounds of limestone awaiting installation Roger Gillman and Peter Wolfson operate U.S. Live Rock, a Florida-based mariculture that supplies the US aquarium market (hobbyist, public aquariums, and academia) with aragonite rock cultured at their leased site off the shores of Florida Keys. In 2013, a novel idea popped into their heads. Why not use their farming site to create an massive artificial reef resembling an universally recognizable shape ... say, a 150ft diameter peace sign? When finished, the Peace Reef will be visible from the air as well as Google Earth satellite images. Gillman and Wolfson's hope is that the Peace Reef will raise public awareness for coral reefs, help supply the Amercian aquarium market with aquacultured live rock as an alternative to Indo-Pacific wild rock, and invite underwater adventurers to dive the Peace Reef thus "reducing the pressure on the adjacent natural reefs frequented by divers." The Peace Reef Project is seeking private donations and corporate sponsors to make their vision a reality. To create an artificial reef of this size requires an estimated 750 tons of quarried aragonite and logistics to install all that rock. Visit the Peace Reef website for more information or if you'd like to contribute. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

Try checking with aquamarin. Bought mine fron there previously. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

Click through to see the images. Or maybe everything looks better sped-up? Bleh. The truth is healthy reef life is awesome any way you record them (so long as you add a cinematic soundtrack, of course). Check out this awesome fast-paced promotional video of Polyp Labs Polyp Booster coral food directed/edited by ThomasVisionReef. While we are not affiliated nor do we endorse this particular product, this video is a great reminder that corals are voracious animals. To learn more about coral nutrition, (re)read Dr. Tim Wijgerde's excellent coral feeding article. View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Researcher Dr Jacob Johansen said that fish rely on swimming for almost all activities necessary for survival, including hunting for food and finding mates. “However, global warming may reduce the swimming ability of many fish species, and have major impacts on their ability to grow and reproduce,†he said. Dr Johansen said that research aimed at understanding the impact of global warming on the commercially important fish species, coral trout, revealed that increasing ocean temperatures may cause large fish to become lethargic, spending more time resting on the bottom and less time swimming in search for food or reproductive opportunities. He said that the study he and his colleagues had undertaken showed that even when individuals do muster up enough energy to swim around, they swim at much slower rate. This lower activity is likely to directly impact their ability to catch food, or visit spawning sites. “The loss of swimming performance and reduced ability to maintain important activities, like moving to a spawning site to reproduce, could have major implications for the future distribution and abundance of these species,†Dr Johansen said. Professor Morgan Pratchett said that the changes to activity patterns and swimming speeds “may directly influence where we will find these species in the future and how many we are able to fish sustainablyâ€. But all is not lost, Dr Johansen said, as there was some evidence that coral trout may be able to adapt to increasing temperatures. “Populations from the northern region of the Great Barrier Reef were a little better than southern populations at tolerating these conditions,†he said. “Coral trout is one of the most important fisheries in the South-East Pacific. If we want to keep this fishery in the future, it is critical that we understand how global warming may impact the species.†“This will allow us to develop management plans that will help to keep the species, and its fisheries, healthyâ€. The research team, which comprises Dr Vanessa Messmer, Dr Darren Coker, and Dr Andrew Hoey, along with Professor Pratchett and Dr Johansen, are planning further experiments to clarify the ability of coral trout to adapt to the rapid changes caused by global warming or if they may be forced to relocate to cooler more southerly waters. Their paper “Increasing ocean temperatures reduce activity patterns of a large commercially important coral reef fish†by J.L. Johansen, V. Messmer, D.J. Coker, A.S. Hoey and M.S. Pratchett is published in the latest issue of the journal Global Change Biology. via ARC Centre of Excellence in Coral Reef Studies View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. The goby meanders around the tank until it finds another lost, lonely soul. Both goby and shrimp move with new-found purpose soon after finding each other. It's amazing how quickly this odd couple bonds and finds a home together. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. This isn't exactly a new discovery, but we haven't seen any mainstream aquarist magazine or blog report about this ... and it's simply too fascinating not to share this fun bit of science. Axolotl keepers may already know about this, but for the rest of us here's the story. Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum) are often thought of as one of the cutest animals on Earth and thus make popular aquarium pets. These Mexican amphibians retain their juvenile frilly puppy-like appearance for their lifetime (a rare condition called neoteny), yet are able to reproduce with other axolotls. Talk about Peter Pan syndrome! Scientists discovered something awesome about axolotls: If you administer the right dosage of iodine, the adorable little water dogs morph into water monsters resembling tiger salamanders! Yep! This is a real life analog of the classic horror/comedy movie where adorable furballs morphed into Gremlins after making contact with water. Mature tiger salamanders. Photo by Carla Isabel Ribeiro Axolotls are a divergent evolutionary branch of salamanders who resemble the juveniles of tiger salamanders. Unlike most salamanders, axolotls lost their ability to produce thyroid stimulating hormones (likely due to environmental adaptation). These hormones are responsible for triggering metamorphosis in other amphibians, so without them, axolotls live their lives in eternal youth. According to wikipedia: Neoteny has been observed in all salamander families in which it seems to be a survival mechanism, in aquatic environments only of mountain and hill, with little food and, in particular, with little iodine. In this way, salamanders can reproduce and survive in the form of a smaller larval stage, which is aquatic and requires a lower quality and quantity of food compared to the big adult, which is terrestrial. If the salamander larvae ingest a sufficient amount of iodine, directly or indirectly through cannibalism, they quickly begin metamorphosis and transform into bigger terrestrial adults, with higher dietary requirements. In fact, in some high mountain lakes also live dwarf forms of salmonids, caused by deficiency of food and of iodine, in particular, which causes cretinism and dwarfism due to hypothyroidism, as it does in humans. Only when axolotls are exposed to hormone-inducing compounds like iodine do their genealogical lineage become unmistakenly apparent. It also interesting to note that this artificially induced metamorphosis creates salamanders that are listless and do not live very long. For more information on this strange phenemenon and a stern lesson why aquarists should not try to make their axolotls metamorphisize, read this article at axolotls.org. Science is often more incredible than fiction. View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Marine biologist Kate Furby is on Palmyra Atoll (near Hawaii) investigating recovery mechanisms for damaged and bleached corals. Of particular interest is Porites superfusa, a SPS with seemingly supernatural resiliency. Her research team has observed this coral remarkably spring back to life, emerging through the algae and sponges covering its tissue-less skeleton many months after "death." She hopes that Porites superfusa and corals like it can teach us how corals might cope with catastrophies. Here is an entertaining interview with Kate Furby by PHD Comics and shared by the National Science Foundation: " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> Zombies in our reef tanks? I've observed this phenomenon over the years, and I suspect many reefkeepers have seen mysterious corals appear out of their live rock too. Perhaps more interestingly, it's always been one of two genera of SPS in my experience: Porites and Leptastrea. After months of apparent lifelessness (algae has overgrown the once-white skeletons), new polyps will emerge and reestablish a colony. Perhaps the secret to these corals' amazing resiliency is their skeletal structure consisting of corallites with elaborate columella providing cryptic coral cells a safe place to "hide" (like a coral apocalypse bunker) until conditions for life are favorable again. View the full article

-

Go check out Ez marine. One of the famous LFS in Taiwan. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

Click through to see the images. From Oregon State University Large study shows pollution impact on coral reefs – and offers solution One of the largest and longest experiments ever done to test the impact of nutrient loading on coral reefs today confirmed what scientists have long suspected – that this type of pollution from sewage, agricultural practices or other sources can lead to coral disease and bleaching. A three-year, controlled exposure of corals to elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus at a study site in the Florida Keys, done from 2009-12, showed that the prevalence of disease doubled and the amount of coral bleaching, an early sign of stress, more than tripled. However, the study also found that once the injection of pollutants was stopped, the corals were able to recover in a surprisingly short time. “We were shocked to see the rapid increase in disease and bleaching from a level of pollution that’s fairly common in areas affected by sewage discharge, or fertilizers from agricultural or urban use,†said Rebecca Vega-Thurber, an assistant professor in the College of Science at Oregon State University. “But what was even more surprising is that corals were able to make a strong recovery within 10 months after the nutrient enrichment was stopped,†Vega-Thurber said. “The problems disappeared. This provides real evidence that not only can nutrient overload cause coral problems, but programs to reduce or eliminate this pollution should help restore coral health. This is actually very good news.†The findings were published today in Global Change Biology, and offer a glimmer of hope for addressing at least some of the problems that have crippled coral reefs around the world. In the Caribbean Sea, more than 80 percent of the corals have disappeared in recent decades. These reefs, which host thousands of species of fish and other marine life, are a major component of biodiversity in the tropics. Researchers have observed for years the decline in coral reef health where sewage outflows or use of fertilizers, in either urban or agricultural areas, have caused an increase in the loading of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. But until now almost no large, long-term experiments have actually been done to pin down the impact of nutrient overloads and separate them from other possible causes of coral reef decline. This research examined the effect of nutrient pollution on more than 1,200 corals in study plots near Key Largo, Fla., for signs of coral disease and bleaching, and removed other factors such as water depth, salinity or temperature that have complicated some previous surveys. Following regular injections of nutrients at the study sites, levels of coral disease and bleaching surged. One disease that was particularly common was “dark spot syndrome,†found on about 50 percent of diseased individual corals. But researchers also noted that within one year after nutrient injections were stopped at the study site, the level of dark spot syndrome had receded to the same level as control study plots in which no nutrients had been injected. The exact mechanism by which nutrient overload can affect corals is still unproven, researchers say, although there are theories. The nutrients may add pathogens, may provide the nutrients needed for existing pathogens to grow, may be directly toxic to corals and make them more vulnerable to pathogens – or some combination of these factors. “A combination of increased stress and a higher level of pathogens is probably the mechanism that affects coral health,†Vega-Thurber said. “What’s exciting about this research is the clear experimental evidence that stopping the pollution can lead to coral recovery. A lot of people have been hoping for some news like this. “Some of the corals left in the world are actually among the species that are most hardy,†she said. “The others are already dead. We’re desperately trying to save what’s left, and cleaning up the water may be one mechanism that has the most promise.†Nutrient overloads can increase disease prevalence or severity on many organisms, including plants, amphibians and fish. They’ve also long been suspected in coral reef problems, along with other factors such as temperature stress, reduced fish abundance, increasing human population, and other concerns. However, unlike factors such as global warming or human population growth, nutrient loading is something that might be more easily addressed on at least a local basis, Vega-Thurber said. Improved sewage treatment or best-management practices to minimize fertilizer runoff from agricultural or urban use might offer practical approaches to mitigate some coral reef declines, she said. Collaborators on this research included Florida International University and the University of Florida. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and Florida International University. View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. The researchers evaluated both the geologic record of past extinctions and recent major events to assess the characteristics of dominant corals under various conditions. They determined that during periods advantageous to coral growth, natural selection favors corals with traits that make them more vulnerable to climate change. The last 10 thousand years have been especially beneficial for corals. Acropora species, such as table coral, elkhorn coral and staghorn coral, were favored in competition due to their rapid growth. This advantageous rapid growth may have been attained in part by neglecting investment in few defenses against predation, hurricanes, or warm seawater. Acropora species have porous skeletons, extra thin tissue, and low concentrations of carbon and nitrogen in their tissues. The abundant corals have taken an easy road to living a rich and dominating life during the present interglacial period, but the payback comes when the climate becomes less hospitable. Researchers from the UHM School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST); the National Marine Fisheries Service (Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, and Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center); NOAA National Ocean Service; and NOAA Coral Reef Watch propose that the conditions driven by excess carbon dioxide in the ocean cause mortality at rates that are independent of coral abundance. This density-independent mortality and physiological stress affects reproductive success and leads to the decline of corals. Some coral species are abundant across a broad geographic range, but the new findings show that this does not safeguard them against global threats, including changing ocean chemistry and rising temperatures. Nearly all the assessments and evaluations of the risk of extinction for a species of coral are made on the basis of how scarce or restricted in range it is. However, the new findings highlight the vulnerability of abundant and widely dispersed corals as well as corals that are rare and/or have restricted ranges. Moving forward, the authors hope to strengthen the case for directly addressing the global problems related to coral conservation. Though it is good to handle local problems, the authors stress, the handling of all the local problems will not be sufficient. Press Release: Kaunana: The Research Publication of the University of Hawai'i at MÄnoa View the full article

-

I could pass u some. What happen to the blue reef chromis? I just bought a few last week as well. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

Nice grey angel !! Seem like it has gain alot of weight. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

A 3ft tiny piece of ocean in my living room

Harlequinmania replied to danccy's topic in Members Tank & Specs

Wa..I believe you are the first user for hydra 52 in Singapore !! -

Click through to see the images. Take a look at the photos above from the Great Barrier Reef. Siganus vulpinus, S. corallinus and S. puellus pairs are cruising the reef grazing algae. While one eats, the other appears to "adopt a posture of vigilance." In other words, one rabbitfish is looking out for his/her companion. This is the first time this behavior - once believed reserved for higher ordered animals - has been documented in fish. For anyone with pairs of con-specific grazing fish like tangs, rabbitfish, angels, or butterflies, have you observed this type of phenomenon in your aquarium? It would not surprise us if this behavior occurs with regularity in our aquariums but goes unnoticed. View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. From the University of California at Sand Diego: Scripps Leads First Global Snapshot of Key Coral Reef Fishes In the first global assessment of its kind, a science team led by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego has produced a landmark report on the impact of fishing on a group of fish known to protect the health of coral reefs. The report, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B (Biological Sciences), offers key data for setting management and conservation targets to protect and preserve fragile coral reefs. Beyond their natural beauty and tourist-attraction qualities, coral reefs offer economic value estimated at billions of dollars for societies around the world. Scripps Master’s student Clinton Edwards, his advisor Jennifer Smith, and their colleagues at the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at Scripps, along with scientists from several international institutions, have pieced together the first global synthesis on the state of plant-eating fish at coral reef sites around the world. These herbivorous fish populations are vital to coral reef health due to their role in consuming seaweed, making them known informally as the “lawnmowers†of the reef. Without the lawnmowers, seaweeds can overgrow and out-compete corals, drastically affecting the reef ecosystem. Among their findings, the researchers found that populations of plant-eating fish declined by more than half in areas that were fished compared with unfished sites. “One of the most significant findings from this study is that we show compelling evidence that fishing is impacting some of the most important species on coral reefs,†said Smith. “We generally tend to think of fishing impacting larger pelagic fishes such as tuna but here we see big impacts on smaller reef fish as well and particularly the herbivores. This is particularly important because corals and algae are always actively competing against one another for space and the herbivores actively remove algae and allow the corals to be competitively dominant. Without herbivores, weedy algae can take over the reef landscape. We need to focus more on protecting this key group of fishes around the globe if we hope to have healthy and productive reefs in the future.†“While these reef fish are not generally commercial fisheries targets,†said Edwards, “there is clear evidence from this study that fishing is impacting their populations globally.†Edwards, a UC San Diego graduate, recently completed his Masters thesis at Scripps where he said his experience and the opportunities he was given to conduct research were unparalleled. The researchers also found that fishing alters the entire structure of the herbivore fish community, reducing the numbers of large-bodied feeding groups such as “grazers†and “excavators†while boosting numbers of smaller species such as algae-farming territorial damselfishes that enhance damaging algae growth. “These results show that fished reefs may be lacking the ability to provide specific functions needed to sustain reef health,†said Edwards. “We are shifting the herbivore community from one that’s dominated by large-bodied individuals to one that’s dominated by many small fish,†said Smith. “The biomass is dramatically altered. If you dive in Jamaica you are going to see lots of tiny herbivores because fishers remove them before they reach adulthood. In contrast, if you go to an unfished location in the central Pacific the herbivore community is dominated by large roving parrotfishes and macroalgal grazers that perform many important ecosystem services for reefs.†The authors argue that such evidence from their assessment should be used in coral reef management and conservation, offering regional managers data to show whether key herbivores are fished down too low and when they’ve successfully recovered in marine protected areas. “This assessment allows us to set management goals in different regions across the globe,†said Smith. “Regional managers can use these data as a baseline to set targets to develop herbivore-specific fisheries management areas. We should be using these important fish as a tool for reef restoration. On reefs where seaweed is actively growing over reefs, what better way to remove that seaweed than to bring back those consumers, those lawnmowers?†In addition to Edwards and Smith, coauthors include Brian Zgliczynski and Stuart Sandin from Scripps; Alan Friedlander of the U.S. Geological Survey; Allison Green of the Nature Conservancy; Marah Hardt of OceanInk; Enric Sala of the National Geographic Society; Hugh Sweatman of the Australian Institute of Marine Science; and Ivor Williams of the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and NOAA through the Comparative Analysis of Marine Ecosystem Organization (CAMEO) program. View the full article

-