-

Posts

8,253 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

31

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Everything posted by Harlequinmania

-

Click through to see the images. Summary of Pedro Rosa's Utopia: ADA 60P 17 gallon aquarium (W60×D30×H36cm) ADA Hornwood Seiryu Stone ADA Amazonia Soil Plants: Topica's Montecarlo, Ludwigia sp. and Eleocharis sp. Aquaplant.nl: Eleocharis Acicularis. Mosses: Topica's Vesicularia ferriei 'Weeping' and Taxiphyllum sp. 'Spiky'. Animals: ~30 Paracheirodon simulans (Green Neon Tetra); 3x Crossocheilus siamensis (SAE - Siamese algae eater); 1x Ancistrus sp.; 1x Otocinclus" sp. "Paraguay; ~10 Caridina cantonensis sp. "Red" (Crystal Red Shrimp) Our admiration for Pedro's aquascaping talent should go without saying once you've watched these videos. But his ability to clearly capture and define his creative process through the camera is equally worthy of respect. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Dr. Tim Wijgerde and Michaël Laterveer are embarking on a new research to discover knowledge and develop a protocol for aquarists, public aquariums, and academic institutions to grow and farm azooxanthellate corals with a notorious captive track record: the carnation corals. To fund the required work, they are seeking the financial contributions of aquarists and the aquarium industry. With emerging interest in azoox reefkeeping, demand for azoox corals by aquarists and public aquaria are expected to increase as well. Wijgerde and Lateveer aim to see what science can do to alleviate the pressure on coral collection. Their research will yield a sustainable protocol to keep and propagate azoox corals in captivity starting with Dendronephthya and Scleronephthya spp. Advanced Aquarist strongly encourages your contribution to this crowd-sourced research. Even $5 will help. Encourage your favorite aquarium brands to make corporate contributions. Spread the word with fellow reefkeepers. Like and share this article on Facebook. Tweet it to the world. This is the very type of progress our hobby needs, and it's led by two of the most credible and capable coral researchers we know. Let's start something special! ♦♦♦ Please visit the Indiegogo project page for information and to contribute to research. ♦♦♦ For reference on the quality of coral research you can expect from your contribution to Wijgerde and Laterveer's research, see: Coral growth under Light Emitting Diode and Light Emitting Plasma: a cross-family comparison Feeding and oxygen affect coral growth: implications for coral aquaculture Zooxanthellae: Biology and Isolation for Scientific Study Zooplankton Feeding by Corals Underestimated Red Light Represses the Photophysiology of the Scleractinian Coral Stylophora pistillata View the full article

-

Keeping Berried Harlequin Shrimp in Breeding Box?

Harlequinmania replied to anmiheng's topic in General Reefkeeping_

There is an article on the net about breeding harlequin shrimp which maybe you can also take a look. You would need rotifer to feed the baby when it hatch. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2 -

Click through to see the images. The Isis Aquarium is 25 gallon acrylic aquarium that measures 31 inches wide and 16 inches in diameter with three 4x8" top openings. The aquarium rests on four wooden feet contoured to fit the curve of the cylinder. The prototype is lit by an off-the-shelf 30" ZooMed Aquasun dual T5 hood. The aquarium does not have any accommodation for filtration; an internal submersible filter appears to be the only practical option as the prototype currently exists. We hope to see further refinements such as a slimmer, more elegant LED hood (possibly enclosed in wood matching its feet) and either a built-in above-tank filter or plumbing access for external filtration. Its designer, David Landguth (Los Angeles, CA) recently successfully completed a Kickstarter campaign with the goal of bringing his product to wide distribution. Watch his Kickstarter video below for a better understanding of the Isis Aquarium. View the full article

-

The first humans to pluck a Caribbean fighting conch from the shallow lagoons of Panama's Bocas del Toro were in for a good meal. (2014-03-19) View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. There are numerous species of anemonefishes, more commonly known to hobbyists as clownfishes, that normally associate with a few species sea anemones. However, these same clownfishes will often times associate with non-anemone invertebrates in the absence of a suitable anemone host. It's an odd but common occurrence in aquaria, and this month I'll give you some information about clownfish-anemone relationships, and show you some examples of their substitute hosts. A pair of the clownfish Amphiprion perideraion, living in their host anemone, Heteractis magnifica. Below is some video of their behavior in their natural habitat. The clownfish-anemone relationship Due to revisions of clownfish taxonomy, various sources report different numbers of clownfish-anemone associations. So, I'll simply say that there are about 30 species of clownfishes, all of which belong to the genus Amphiprion, with the exception of one species that belongs to the genus Premnas. Regardless of the exact number, all of these are obligate symbionts of ten species of sea anemone belonging to the genera Cryptodendrum, Entacmaea, Heteractis, Macrodactyla, and Stichodactyla. In other words, these fishes are always found living amongst the stinging tentacles of these anemones in the wild, except when very young. Clownfishes may seem to be perfectly fine without an anemone host when kept in aquaria, but this is not the case on the reefs they inhabit. Regardless, their natural relationship is considered to be a mutualistic symbiosis, because both the clownfishes and their anemone hosts live together in such a way that both receive benefits from each other. These increase both organisms' chances of survival and their reproductive success. Through methods that I'll cover below, these fishes are able avoid being stung and killed/injured by their host anemone. So, when threatened by predators, clownfishes can move into the stinging tentacles of their host, which is a very effective deterrent. Thus, the fishes are granted a safe haven when living with an anemone. According to Fautin (1991), the fishes may also feed on an anemone's egestate, which is any partially or undigested material spat out by an anemone if it eats more than it can handle. And, the fishes' egg are afforded some degree of protection, as they are typically laid on the substrate underneath their host anemone's disc. Clownfishes' egg are typically laid under the disc of their host anemone, giving the eggs some protection, as well. On the other hand, clownfishes oftentimes aggressively chase off any fishes or invertebrates that attempt to feed on their host, especially butterflyfishes (Fautin, 1991 and Porat & Chadwick-Furman, 2004). Likewise, as many aquarists have experienced, many clownfishes will also defend their host from human hands and arms that get too close by charging and nipping at them. This is especially so for larger species, like Premnas biaculeatus, which can be downright mean to owners and other fishes alike. Clownfishes may also feed their host at times by taking food items into an anemone's tentacles. Once sated in an aquarium, I've seen numerous clownfishes take flake food, mysis shrimp, bits of chopped meat, and even small feeder fishes to their host. I also found an article at Animal World (undated) stating that some captive clownfishes will knock or drag non-cleaning species of shrimp into their host. Host feeding has also been reported in the wild (Allen, 1972 and Fautin, 1991), but apparently is not common. Aside from potentially delivering food items to their host, it has been found that clownfishes also provide nitrogen to their host in the form of ammonia, reducing a host's need to feed (Roopin & Chadwick, 2009). Fishes excrete ammonia as a waste product, but their hosts can absorb it from the waters around them, where concentrations may be nearly 50% above background levels when clownfishes are present (Roopin et al., 2011). Lastly, a very recent study by Szczebak et al. (2013), found that the constant swimming and wiggling activities of clownfishes helps to increase water movement around the tentacles of some anemones. This in turn increased oxygen available to the host, thus aiding them in yet another way. How clownfishes can do it Each species of clownfish will only go to certain species of host anemones in the wild, and these species-specific pairings have been well documented. In fact, you can find an excellent resource (Fautin & Allen, 1992) that covers these pairings here, and it's free. So, as juveniles, clownfishes must find a host anemone that's available and of the right species as quickly as possible in order to increase their chances of survival, and it has been shown that they can apparently smell them. In the lab, Murata et. al. (1986) found that a crude mucous extract from the host anemone Radianthus kuekenthali (now known as Heteractis crispa) would elicit the attraction of the clownfish A. perideraion. It would also elicit the hallmark odd swimming pattern that clownfishes frequently display when occupying a host. They also found that a chemical they extracted from the anemone, which they named amphikuemin, would get the same results. Continuing on, they likewise found that different species of clownfishes recognized chemical cues from the same host species of anemone, and from different host species, too. So, it seems that's how things get started. But, how do they "move in"? It has also been experimentally shown that toxins isolated from various anemones will outright kill many clownfishes exposed to them. So, it seems clear that clownfishes aren't getting stung and showing some sort of immunity to the toxins, rather they aren't getting stung by their hosts (Mebs, 1994). Apparently it all has to do with the mucus slime coat the fishes produce. Through experiments using juvenile clownfishes that had not been in contact with an anemone, Miyagawa (2010) found that several species of clownfish found in Japanese waters had an innate protection from being stung. Miyagawa also reiterated that juveniles recognize their species-specific hosts via chemical factors produced and released by them, and reported that visual cues did not seem to play a significant role in host identification. Still, it seems that no one has determined if the fishes' slime coat contains chemicals that inhibit the discharge of an anemone's nematocysts (stinging cells), or if it just lacks any chemicals that would stimulate their discharge (Mebs, 2009). Clownfishes that get confused With all that covered, now let's get to some things that aren't in the literature, namely clownfishes doing things in aquariums that they don't do in the wild. They sometimes move into host anemones that don't normally host them. They sometimes take up residence in or on various other cnidarians. And, they sometimes hang out on top of giant clams, too. Again, in aquariums clownfishes will often find a substitute or surrogate host if no appropriate anemone is available, which is something they never do in the wild. I have searched and searched for anything covering how they are able to do this, but came up with nothing. Sometimes this is seen as a particular species of clownfish taking up residence in an anemone that does host clownfishes, but just not that species of clownfish. For example, the bubble-tip anemone, Entacmaea quadricolor, normally hosts 13 species of clownfish, but not Amphiprion leukocranos or A. ocellaris (Fautin & Allen, 1994). However, in aquariums, these two species will oftentimes move into a bubble-tip when their normal hosts are absent. In fact, I don't recall any A. ocellaris that wouldn't do so, with one exception (sort of) that I'll get to below. In the case of A. leukocranos, Fishbase (undated) reports that this species may be a hybrid between A. chrysopterus and A. sandaracinos, and the bubble-tip anemone does host A. chrysopterus. So, maybe that has something to do with its ability to move in. As best as I can tell, there's no explanation for A. ocellaris doing so, though. Here are Amphiprion leukocranos and A. ocellaris living in bubble-tip anemones (one lacking bubbles, which is not unusual for this anemone). These aren't the only two species that do this sort of thing, either. I've been a reef aquarist for over 20 years now, but have never seen a clownfish of any sort take up residence in the Caribbean/Western Atlantic not-host-to-any-clownfish anemone Condylactis gigantea - except for this black and white A. ocellaris. This was around 1993, in a 55-gallon mixed reef aquarium I had. Ah, Mother Nature. Always fooling around... The clownfish Amphiprion ocellaris living in the non-host anemone Condylactis gigantea. Lastly, another related personal anecdote. I have some aquariums at school and put a bubble-tip anemone in one of them, along with a pair of tank-raised A. ocellaris. They never even looked at it. For months it was like they didn't even know it was there, which is unusual in my experience. In the summer, I typically remove the few fishes from the school aquariums and bring them home where I can feed them daily without relying on an automatic feeder. So, I brought the clownfish home and put them in my anemone-less 125-gallon mixed reef tank. When the holidays were over it was time for the clownfish to go back to school. So, I trapped them and moved them back to their original aquarium. The next day both were in the anemone. Makes no sense at all... As I said above, clownfishes will also oftentimes move into (or just on) a variety of non-anemone cnidarians. Some of these, such as soft corals like Sarcophyton spp. and Sinularia spp. don't sting fishes. However, some of these substitute hosts pack a very strong sting for a coral, leaving us to wonder, once again, how and why the clownfishes do this. In some cases a substitute host, like Catalaphyllia jardinei or Euphyllia spp., does indeed have long tentacles with relatively strong stings. Thus, a confused clownfish may indeed be afforded the same protection from predators it would receive from a host anemone. I will assume that at least some of the benefits to a host covered above would be received by such a coral host, too. However, there are many other pairings that just don't make sense. See the pictures below for some examples. Clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Catalaphyllia jardinei. Clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Euphyllia sp. More clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Euphyllia sp. Clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Goniopora sp. Clownfishes living amongst the tentacles of the stony coral Plerogyra sinuosa, and on top of the coralsTrachyphyllia geoffroyi and Acanthastrea sp. Clownfishes living amongst the branches of the soft corals Sinularia sp. and Alcyonium sp. Clownfishes living amongst the polyps/on top of the soft coral Sarcophyton sp. Clownfishes living on top of the corallimorphs Discosoma sp. and Rhodactis inchoata. As noted, some of these don't make much sense, but they can get even stranger. As stated, they'll sometimes decide to live on top of giant (tridacnid) clams. Even more peculiar is the fact that sometimes they'll do this even when a more suitable cnidarian host is available. So, in these cases the clownfishes are offered no protection from predators, and any benefits of the relationship apparently go only to the "host" clam. Tridacnid clams do not seem to be harmed when this happens. However, there is something of an acclimation period in which the clams jerk their mantle tissue inward, over and over, every time a clownfish touches them or passes over their simple eyes. Eventually the clams become accustomed to this overhead activity though, and react far, far less or not at all to a clownfish's presence. This sort of thing happens much more than you might believe, and again, you can see the pictures below for examples. Clownfishes living on top of the giant clam Tridacna derasa. Clownfishes living on top of the giant clam Tridacna gigas. All of this mismatching does raise one big question in my mind. While I've seen countless clownfishes that seemed to be perfectly happy and healthy in aquariums with nothing that could serve as a normal or abnormal host, are they really happy? If clownfishes are always found living with host anemones in the wild, and will use something like a clam as a substitute in a pinch, it just makes me wonder what it must be like to have nothing at all. Frankly, I don't see how it could be possible for them to not be stressed by the lack of a host. But, again, I've certainly seen plenty that didn't seem to be to upset about it. Food for thought... One more thing While it's not specifically related to the above information, I've got one more thing that's too weird to not bring up. Remember my clownfish that I moved from school to home? While they hadn't paid any attention to the anemone or corals in their aquarium at school, within a matter of days after bringing them home they split up. One of them moved into a soft coral (Sinularia sp.) and the other moved onto a 6" Tridacna derasa. Soon after one of the clownfish took up residence on top of my clam, my cherub angelfish (Centropyge argi),which had never paid any attention to the clam, started hanging out with the clownfish. In fact, it started acting like the clownfish, as in mimicking its goofy movements over the clam. I certainly had never seen anything like this, and enjoyed watching them quite a lot. Pretty funny, really, and you have to see this to believe it: References Allen, G.R. 1972. The Anemonefishes: Their Classification and Biology. TFH Publications, Neptune, NJ. 288pp. Animal World, undated. Clarkii Clownfish. URL: http://animal-world.com/encyclo/marine/clowns/clarkii.php Fautin, D.G. 1991. The anemonefish symbiosis: what is known and what is not. Symbiosis: 10, p.23-46. Fautin, D.G. and G.R. Allen. 1994. Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones. Tetra-Press, Mella, Germany. 157pp. Fautin, D.G. and G.R. Allen. 1992. Field Guide to Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones. URL: http://www.nhm.ku.edu/inverts/ebooks/intro.html Fishbase. undated. Amphiprion leucokranos. URL: http://www.fishbase.org/summary/9207 Kai, T.Y. 2012. A clownfish and its anemone play host to their unorthodox angelfish friend. Reef Builders. URL: http://reefbuilders.com/2012/07/09/clownfish-anemone-angelfish/ Mebs, D. 2009. Chemical biology of the mutualistic relationships of sea anemones with fish and crustaceans. Toxicon: 54(8), p.1071-1074. Mebs, D. 1994. Anemonefish symbiosis: Vulnerability and resistance of fish to the toxin of the sea anemone. Toxicon: 32(9), p.1059-1068. Miyagawa, K. 2010. Experimental analysis of the symbiosis between anemonefish and sea anemones. Ethology: 80(1-4), p.19-46. Murata, M., K. Miyagawa-Kohshima, K. Nakanishi, and Y. Naya. 1986. Characterization of compounds that induce symbiosis between sea anemone and anemone fish. Science: 234, p.585-587. Porat, D. and N.E. Chadwick-Furman. 2004. Effects of anemonefish on giant sea anemones: expansion behavior, growth, and survival. Hydrobiologia: 530/531, p.513-520. Roopin, M. and N.E. Chadwick. 2009. Benefits to host sea anemones from ammonia contributions of resident anemonefish. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology: 370(1-2), p.27-34. Roopin, M., D.J. Thornhill, S.R. Santos, and N.E. Chadwick. 2011. Ammonia flux, physiological parameters, and Symbiodinium diversity in the anemonefish symbiosis on Red Sea coral reefs. Symbiosis: 53(2), p.63-74. Szczebak, J.T., R.P. Henry, F.A. Al-Horani, and N.E. Chadwick. 2013. Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night. Journal of Experimental Biology: 216:970-976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648. View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. In this video, the owner (presumably of a pet store) is seen not only stroking and hand-feeding the huge eel but also petting the inside of its mouth! As bizarre and scary as this footage, it's actually one of several videos we've seen of caretakers handling massive green moray eels (take this video for example) without incident. Then again, we've also seen our fair share of the terrible flesh wounds these eels can inflict on people (photos we will gracefully not share, but google them if you dare). While this video is very cool and arguably even inspiring, please do not try this. Don't make us post the gruesome bloody eel bite photos. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

you can consider Fluval pump or reef octopus water buster which is quite reliable as well.

-

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

You will be the first one to know. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2 -

Click through to see the images. As this sensational video shows, culling lionfish is not without its risks. Jason endorses support of organizations like REEF.org to help with their marine conservation and education programs. This post has admittedly little to do with aquariums except one very important lesson (one we've made many times before): NEVER dispose of your aquarium contents - livestock, substrate/decoration, even water - into local bodies of water. Irresponsible actions like this not only potentially upend native ecosystems with invasive species but also endanger people who have to clean up your mess. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Unprecedented levels of biological diversity underscores value in protecting Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Deep coral reefs in PapahÄnaumokuÄkea Marine National Monument (PMNM) may contain the highest percentage of fish species found nowhere else on Earth, according to a study by NOAA scientists published in the Bulletin of Marine Science. Part of the largest protected area in the United States, the islands, atolls and submerged habitats of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) harbor unprecedented levels of biological diversity, underscoring the value in protecting this area, scientists said. Hawaii is known for its high abundance of endemic species -- that is, species not found anywhere else on Earth. Previous studies, based on scuba surveys in water less than 100 feet, determined that on average 21 percent of coral reef fish species in Hawaii are unique to the Hawaiian Archipelago. However, in waters 100 to 300 feet deep, nearly 50 percent of the fish scientists observed over a two-year period in the monument were unique to Hawaii, a level higher than any other marine ecosystem in the world. The study also found that on some of PMNM's deeper reefs, more than 90 percent of fish were unique to the region. These habitats can only be accessed by highly trained divers using advanced technical diving methods. "The richness of unique species in the NWHI validates the need to protect this area with the highest conservation measures available," said Randy Kosaki, PMNM's deputy superintendent and co-author of the study. "These findings also highlight the need for further survey work on the monument's deeper reefs, ecosystems that remain largely unexplored." Data for the study was collected during two research expeditions to the NWHI aboard the NOAA Ship Hi'ialakai in the summers of 2010 and 2012. Some of the unique fish species that were observed include: Redtail Wrasse (Anampses chrysocephalus), Thompson's Anthias (Pseudanthias thompsoni), Potter's Angelfish (Centropyge potteri), Hawaiian Squirrelfish (Sargocentron xantherythrum), Chocolate Dip Chromis (Chromis hanui), Masked Angelfish (Genicanthus personatus), and Blueline Butterflyfish (Chaetodon fremblii). Journal Reference: Kane, Corinne; Kosaki, Randall K; Wagner, Daniel. High levels of mesophotic reef fish endemism in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Bulletin of Marine Science, February 2014 DOI: 10.5343/bms.2013.1053 [via NOAA] View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Water Dragon Advanced aquarists usually aren't the biggest fans of artificial aquarium decorations, but I think most of us would make an exception for this ... A year ago, professional German aquarium designer and consultant Oliver Knott entered this planted aquarium work of art into the aquscaping competition, The Art of the Planted Aquarium. His unconventional design did not win that year, but the "Dragon Hunter Scape" aquarium has definitely made a lasting impression on anyone who has seen it. The dragon was painstakingly sculpted by Giulio Golinelli (Italy) using polymer clays and acrylic paint over a metal substructure. The intricate details on the dragon, including the above-water island on its back, are unspeakably beautiful. Oliver Knott then surrounded the dragon with choice rock and aquatic plants to complete a fantasy aquascape unlike any other. Here is a video of the making of Dragon Hunter Scape: " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> Oh yeah, Oliver Knott also submitted this aquarium into the competition. This man exudes creativity! View the full article

-

Click through to see the images. Reproduced from Coral Reefs open access paper: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00338-013-1101-6 The corallivorous flatworm Amakusaplana acroporae: an invasive species threat to coral reefs? Benjamin C. C. Hume1, Cecilia D’Angelo1, Anna Cunnington1, Edward G. Smith1, 2 and Jörg Wiedenmann1 (1) Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, National Oceanography Centre Southampton (NOCS), European Way, Southampton, SO143ZH, UK (2) Present address: Centre for Genomics and Systems Biology, New York University, Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129 188, Abu Dhabi, UAE Abstract Fatal infestations of land-based Acropora cultures with so-called Acropora-eating flatworms (AEFWs) are a global phenomenon. We evaluate the hypothesis that AEFWs represent a risk to coral reefs by studying the biology and the invasive potential of an AEFW strain from the UK. Molecular analyses identified this strain as Amakusaplana acroporae, a new species described from two US aquaria and one natural location in Australia. Our molecular data together with life history strategies described here suggest that this species accounts for most reported cases of AEFW infestations. We show that local parasitic activity impairs the light-acclimation capacity of the whole host colony. A. acroporae acquires excellent camouflage by harbouring photosynthetically competent, host-derived zooxanthellae and pigments of the green-fluorescent protein family. It shows a preference for Acropora valida but accepts a broad host range. Parasite survival in isolation (5–7 d) potentially allows for an invasion when introduced as non-native species in coral reefs. Introduction Coral reefs, one of the most biodiverse and productive ecosystems in the world, are sensitive to a range of perturbations including the potentially devastating effects of corallivory, defined as the direct assimilation of live coral tissue (Hughes et al. 2007; Rotjan and Lewis 2008). Fatal infestations of aquarium-cultured acroporid corals with corallivorous flatworms/AEFWs have been globally reported (Electronic Supplemental Material, ESM Table 1, Fig. 1). Early stages of infestations with these well-camouflaged AEFWs often manifest as pale ‘bite marks’ (Nosratpour 2008; ESM Table 1). Most recently AEFWs from two US aquaria were described as a new species (Amakusaplana acroporae) within the phylum Platyhelminthes (Rawlinson et al. 2011), which was subsequently found on A. valida in one natural location off Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef (GBR) (Rawlinson and Stella 2012). The guts and parenchyma of A. acroporae contained nematocysts and zooxanthellae, suggesting that the damage to the corals is due to feeding by the worms (Rawlinson et al. 2011; Rawlinson and Stella 2012). Another Acropora-associated worm is an acoel from the phylogenetically distant taxon Waminoa (phylum Acoelomorpha), which shows a striking phenotypic similarity to A. acroporae (Matsushima et al. 2010), making it difficult to assign the reported AEFW infestation to one or the other species. Also, other representatives of Waminoa live epizoic on corals; however, there are no reports on them being corallivores, and their zooxanthellae are not derived from corals (Barneah et al. 2007). They are thought to consume only coral mucus but may harm the coral by shading and related negative effects on the coral’s photophysiology when occurring in high numbers (Barneah et al. 2007; Haapkylä et al. 2009; Naumann et al. 2010). Although A. acroporae has been found on the GBR, the natural origin and biogeographic range of the aquarium strains of AEFWs are unclear and no natural predators are known, making it difficult to control infestations in land-based Acropora cultures. Reports of aquaria strains of AEFWs include regions close to natural coral reefs such as Florida, Thailand or Hong Kong (Fig. 1), raising the question whether AEFWs represent a risk for natural coral communities if released in the environment. The introduction of non-native species in natural ecosystems including coral reefs may have dramatic consequences, and a significant number of ornamental species have become invasive in aquatic ecosystems (Padilla and Williams 2004). The invasion, for instance, of the Mediterranean Sea by the macroalga Caulerpa taxifolia (Wiedenmann et al. 2001) or the Caribbean Sea by the lionfishes Pterois sp. (Betancur-R et al. 2011) was triggered by the release of aquarium strains. Fig. 1 Global distribution of AEFW infestations of land-based coral cultures reported on the internet (numbers 1–16) and in scientific literature (letters A–D). Locations in proximity to coral reefs are highlighted by boxes in bold style. Black spots show the distribution of tropical coral reefs. The letter (E) marks the location at which A, acroporae was found in the wild (Rawlinson and Stella 2012) To judge the danger that AEFWs represent as potential invasive species for natural coral reefs, we studied the biology of an AEFW strain obtained from the ornamental trade in the UK. We applied molecular taxonomy approaches to identify the species, analysed host preference, feeding behaviour, association with zooxanthellae, effects on the host physiology and survival times in the absence of hosts. Methods Culture and aquarium experiments An AEFW strain acquired from a local ornamental trader in Southampton (UK) was co-cultured for 6 months with a diverse range of acroporids and numerous other coral species (ESM Table 2) in a separated compartment of the experimental coral mesocosm of the Coral Reef Laboratory at the National Oceanography Centre Southampton (D’Angelo and Wiedenmann 2012). Host preference was judged using a classification scheme shown in ESM Table 2. For subsequent studies, AEFWs were dislodged from the host by a seawater jet. Survival in the absence of host corals was evaluated by maintaining ten isolated specimens in a partially shaded compartment without access to corals. To test the response of the AEFWs to increased temperatures, infested fragments of Acropora sp. were subjected to a heat stress treatment as described in (Wiedenmann et al. 2013). Horizontally growing Acropora millepora replicate colonies (infested and non-infested) were turned by 180°, and light acclimation was monitored through the fluorescence increase in the newly light exposed branch surface (D’Angelo et al. 2008). Molecular identification of AEFW and zooxanthellae Genomic DNA (gDNA) was prepared from a pool of 6 AEFWs collected from an A. millepora colony, the infested host colony itself and a co-cultured Acropora microphthalma colony using a protocol described in (Hume et al. 2013). Phylotyping of zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium spp.) in the corals and in the AEFW was conducted by amplifying, cloning and sequencing of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 ribosomal DNA using zooxanthellae-specific primers (ESM Table 3) (Hume et al. 2013; Savage et al. 2002). Sequences were deposited in Genbank (accession numbers JN711475–JN711498). The 18S rDNA region of the AEFW genomic DNA was amplified as two overlapping fragments, using primers designed against conserved regions of polyclad 18S sequences (ESM Table 3). A primer pair to amplify a 618-bp fragment of the 28S region was developed using polyclad 28S sequences available in GenBank (ESM Table 3). Sequences were deposited in Genbank (accession numbers JN711499–JN711500). Phylogenetic analysis of 18S and ITS2 sequences was performed using MEGA 5 (Tamura et al. 2011). Sequences were aligned using ClustalW, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) methods. Analysis was performed to infer an optimal nucleotide substitution method. For 18S analysis, a Tamura-Nei with gamma distribution and 5 rate categories were selected based on Akaike Information Criterion. ITS2 sequences were analysed using the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano model with equal rates. The certainty of ML nodes was tested with bootstrap analysis (100 replications). Photographic documentation, fluorescence measurements and microscopy Coral fluorescence was imaged using a yellow longpass filter and a ~450-nm excitation light source (Nightsea, Andover, USA). Microscopic close-ups were obtained as described in (D’Angelo et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2013). Photosynthesis efficiency of zooxanthellae was determined by pulse amplitude modification (PAM) fluorometry using a Diving-PAM (Walz) for a pool of 5 AEFW specimens. Fluorescence spectra were recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, USA) (D’Angelo et al. 2008, 2012). Results and discussion After co-culturing the AEFW strain with a diverse range of acroporids and fifteen other scleractinian coral species for 6 months in a separated compartment of our experimental coral mesocosm (D’Angelo and Wiedenmann 2012), the AEFWs were still exclusively found on acroporid corals (ESM Table 2). The highest to lowest host preference was as followed: A. valida > A. millepora > A. pulchra > A. polystoma > A. yongei > A. gemmifera > A. microphthalma > A. tortuosa. The AEFWs, reaching a size of up to ~6 mm, were always found attached to the shaded branch sides. Microscopical inspection revealed the excellent camouflage of the AEFWs that mimics both the colour and pigment distribution of the host (Fig. 2a, c; ESM Fig. 1a). Due to their camouflage, the AEFWs could be easily overlooked, but their previously described characteristic pale ‘bite marks’ on the branch underside (ESM Table 1) turned out to be reliable indicators of an infestation (Fig. 2e, ESM Fig. 1a). As described by Rawlinson et al. (2011), another clue to the presence of the parasite was clusters of ~5 to ~90 eggs found only on bare skeleton with close proximity to live coral tissue (ESM Fig. 1b-c). The parasites appear to be rather stationary, and a single individual was observed for 5 weeks on a ~5 cm replicate colony of A. millepora before it was removed for experimental purposes. The activity of this specimen, restricted to the underside of the branch, had a significant effect on the overall physiology of the host coral, essentially preventing it to acclimatise to higher light levels (D’Angelo et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2013) by increasing the accumulation of GFP-like proteins in the light exposed branch side (Fig. 3a). Accordingly, infested colonies were less fluorescent as compared to healthy counterparts (Fig. 3b, c; ESM Fig. 2). Hence, host fluorescence can be used as a further indicator of the presence of the parasites, underlining the potential of GFP-like proteins to serve as stress indicators for corals (D’Angelo et al. 2012). Fig. 2 Acquired camouflage strategy of the AEFW. a, b Micrograph of A. pulchra with a representative AEFW of the UK aquarium strain attached. c, d Images of the isolated parasite. e, f Close-up photographs of a typical ‘bite mark’ left by the parasite in the tissue of the branch underside of A. pulchra. Photographs were acquired under the microscope under white light conditions (a, c, e) and in the fluorescence mode using a CFP/dsRed filter set (b, d, f). Chlorophyll fluorescence shows in red; the fluorescence of the cyan apulFP583 appears in blue. g Fluorescence emission spectra (λ exc = 420 nm) of the host coral tissue (A. pulchra, dotted line) and of the isolated parasite (solid line) Fig. 3 Effect of AEFW infestation on host fluorescence. a Time course of high light acclimation of infested and non-infested replicate colonies of a red colour morph of A. millepora. The increase in host tissue fluorescence emission (λ ex 530 nm, λ max em = 597 nm) per area is shown. The accumulation of the red fluorescent protein amilFP597 (D’Angelo et al. 2008) in the upper branch area was recorded after this previously shaded side was exposed to light. b Photographs of the daylight appearance (above) and the green fluorescence (below) of replicate colonies of a green colour morph of A. millepora during different stages of infestation ranging from healthy (left), over infested (middle) and to dead (right). c Quantitative comparison of the content of the GFP-like protein amilFP512 in the colonies depicted in b expressed as fluorescence emission per area (D’Angelo et al. 2008) Interestingly, the AEFWs collected from A. pulchra show fluorescence patterns perfectly matching those of the host, with the coral fluorescence being derived from the cyan GFP-like protein apulFP583 (D’Angelo et al. 2008) and red chlorophyll fluorescence of zooxanthellae (Oswald et al. 2007) (Fig. 2). In contrast, depending on their developmental stage, eggs and embryos show only a weak blue or orange fluorescence under UV (365 nm) excitation (ESM Fig. 1c). The absence of fluorescence in the feeding marks in the coral tissues proposes that the parasites extract the fluorescent pigments from the host (Fig. 2f). The cyan fluorescent pigments appear to be evenly distributed in the parenchyma of the parasites, suggesting an incorporation of host pigments in their functional form to perfect the camouflage of the parasite (Fig. 2b, d). Such strategy could be facilitated by the high stability and slow turnover of coral GFP-like proteins (Leutenegger et al. 2007). Molecular analysis proved that the algal cells in the AEFWs from an A. millepora colony are zooxanthellae. The distribution of Symbiodinium clades in the AEFW closely matched the host coral’s algal community and was dissimilar to the one of co-cultured A. microphtalma (Fig. 4a), providing evidence that the parasites acquire zooxanthellae from the host by feeding. This is further supported by the lack of zooxanthellae in the feeding marks (Fig. 2e; ESM Fig. 1a). A heat-stressed AEFW individual was observed to release most of its zooxanthellae within a few seconds after contracting movements (presumably via the pharynx), demonstrating that at least most of the algal cells are contained in the intestine (Fig. 4b, c). The photosynthetic efficiency F v/F m > 0.5 determined for AEFW specimens indicates that their zooxanthellae are photosynthetically competent and might provide the parasites with nutritional benefits. Polyclad flatworms are known to be able to starve for months (Chintala and Kennedy 1993). Interestingly, isolated AEFWs without access to the host died after 5–7 d, suggesting that the algae do not represent a significant energy source for the animals but are most likely maintained solely for camouflage purposes. This remarkable camouflage strategy presumably represents an evolutionary adaptation of A. acroporae to the acroporid host. In this context, it is interesting to note that the visually similar camouflage of the Acropora-associated Waminoa representative may be the result of convergent evolution since acoels do not have branched guts (Hyman 1951). Fig. 4 Composition of the zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium spp.) community of an infested colony of A. millepora, of the associated AEFWs and of a co-cultured A. microphthalma colony. a Frequencies of subclades (C21, C3, Cu) were deduced from the detection frequency of the respective sequences among cloned ITS2 fragments. b, c Photographs of a heat-stressed AEFW after expulsion of the zooxanthellae. Images were acquired under white light ( and in the fluorescence mode ©. Red chlorophyll fluorescence of zooxanthellae © was documented by the use of a TRITC filter set. Expelled Symbiodinium cells (exS) are visible in the upper right corner of panels b, c Sequence analyses of the 18S rDNA region demonstrated that the UK AEFW strain groups within the cotylean clade of polyclad flatworms (ESM Fig. 3a), ruling out the phenotypically similar Acropora-associated Waminoa sp. from Okinawa (Matsushima et al. 2010). Analysis of the 28S rDNA region identified the UK strain as the recently described A. acroporae, an AEFW from two US aquaria and from one natural location on Lizard Island (Rawlinson et al. 2011; Rawlinson and Stella 2012) (ESM Fig. 3b). Our 28S rDNA sequence showed a 100 % identity to the Virginia strain of A. acroporae, but could be distinguished in three shared residues from the New York and the Lizard Island strains. These nucleotide substitutions may indicate that at least two molecularly distinct A. acroporae strains are widely distributed in aquaria. Our global survey of reported AEFW infestations (Fig. 1, ESM Table 1) together with the results of the present paper revealed that many of the unidentified AEFWs show characteristics of A. acroporae such as exclusive preference for a diverse range of acroporids, excellent camouflage, preferred occurrence on the shaded branch sides, the typical ‘bite marks’ and egg clusters being deposited on dead skeletons (ESM Table 1). A. acroporae was considered responsible for the loss of Acropora colonies at Birch Aquarium (USA) (Nosratpour 2008; Rawlinson et al. 2011). Taken together, these data suggest that A. acroporae is globally distributed in land-based coral cultures, including regions close to natural coral reefs such as Florida, Thailand or Hong Kong (Fig. 1). We conclude that due to the broad range of accepted host coral species with a high preference for the cosmopolitan A. valida, the excellent camouflage and the ability to survive at least 5 days without host, A. acroporae has the potential to become a dangerous invasive species when released to an environment to which it is non-native. To better categorise this potential risk, further data on the biogeographic range of A. acroporae in reefs around the globe, on its natural predators and on its genetic diversity in captivity are urgently required. View the full article

-

what brand of bio pallets is good?

Harlequinmania replied to tippy's topic in New to the Marine Aquaria Hobby

Np biopallet is proven, but the rest of the brand in the market work as well since I believe they are all using the same material source. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2 -

Yes u need to use transformer but is not cheap. Last I bought mine for close to 100 buck at sim lim. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

Click through to see the images. Before I go into the relationship between amino acids and corals, I would first like to address the following question: what are amino acids? Basically, amino acids belong to a class of organic compounds that is essential to all life. Amino acids form the building blocks of proteins, which in turn have essential functions in living organisms. Twenty two different amino acids exist, but only 21 are found in eukaryotes, i.e. animals, plants, fungi and protists. Although bacteria, plants, and fungi can synthesize most amino acids, animals cannot produce several of them in sufficient quantities to meet their metabolic needs (Shinzato et al. 2014). For example, humans can synthesize 11 amino acids in sufficient quantities, whereas the other 9 must be acquired through the diet. These 9 amino acids are therefore known as essential amino acids, and include histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan and valine. Table 1. Overview of the 22 known amino acids, of which 9 cannot be synthesized by humans. Essential Non-essential Histidine Alanine Isoleucine Arginine* Leucine Asparagine Lysine Aspartic acid (Aspartate) Methionine Cysteine* Phenylalanine Glutamic acid (Glutamate) Threonine Glutamine* Tryptophan Glycine Valine Ornithine* Proline* Selenocysteine* Serine* Tyrosine* Pyrrolysine** *Essential only in certain cases (Reeds 2000; Fürst and Stehle 2004), **Found only in certain bacteria and archaea (Srinivasan et al. 2002). Although each amino acid is chemically different, they all have the same basic structure. On one side of the molecule, they have what is called an amine group (NH2), hence their name. On the other side, we find a carboxyl group (COOH), which gives amino acids their acidic properties. The amine and carboxyl groups are fused with a carbon atom, together with a variable side chain ® that is different for each amino acid. The common chemical formula for amino acids is R-CH(NH2)-COOH. In living cells, amino acids can be linked together to form proteins, a process known as protein biosynthesis (also called biogenesis or anabolism). This is done by linking the amine and carboxyl groups of two amino acids together, where a hydrogen atom (H+) is split from the amine group, and a hydroxyl group (OH-) is removed from the carboxyl group. Thus, this reaction generates water (H2O). Protein biosynthesis occurs when cells translate genetic information into proteins, reading the genetic code stored in DNA letter by letter (or actually, three letters at a time), where each three-letter combination corresponds to a specific amino acid. When several amino acids are linked together in a living cell, this larger molecule is called a peptide. Proteins are larger versions of peptides, in which hundreds of amino acids are linked together. After this linkage, a protein has to be chemically modified and folded into complex shapes to allow it to function inside or outside the cell, as a structural part of a cell membrane, a hormone, an antibody or an enzyme. Basic structure of an alpha amino acid, with the amine group (NH2) shown on the left, and the acidic carboxyl group (COOH) on the right. The R indicates a side chain which varies between different amino acids (image: Y. Mrabet). Sources of amino acids, with a focus on corals Now that we know that amino acids are essential components of living systems, the next question is how organisms obtain these. As mentioned above, a source of amino acids is biosynthesis. In addition, amino acids can be acquired from the external environment. For the rest of this article, I will focus on stony, or scleractinian corals (order Scleractinia). Biosynthesis Just like proteins can be produced from individual amino acids, so too can amino acids themselves be synthesized by living organisms. The building blocks, or substrates, for amino acid biosynthesis can be other acids (such as 3-phosphoglycerate and oxaloacetate) or amino acids themselves. Microorganisms lie at the basis of this all, as they can use inorganic nitrogen in the form of nitrogen gas (N2) to produce ammonia/ammonium (NH3/NH4+), the basic nitrogen ingredients for global amino acid synthesis. Ammonia and ammonium, in turn, are converted into organic form by higher organisms as the amino acids glutamate and glutamine. Examples of such higher organisms are plants, dinoflagellates including zooxanthellae, and possibly also Aiptasia spp., tropical anemones that are considered pests in marine aquaria (also see Wijgerde 2012). Corals can also produce their own amino acids, and unlike most animals, at least some corals can synthesize the essential ones. The ability to produce (essential) amino acids seems to vary between coral species, however. Fitzgerald and Szmant (1997) conducted tracer experiments with radioactive glucose, and found that five different coral species (Montastraea faveolata, Acropora cervicornis, Porites divaricata, Tubastraea coccinea and Astrangia poculata) were all able to synthesize at least 15 different amino acids, of which 8 essential ones. However, analysis of all the Acropora digitifera genes-the so-called genome-revealed that this species can only synthesize ten non-essential amino acids except cysteine, and not the essential ones (Shinzato et al. 2011). Porites australiensis, in turn, does seem to produce cysteine (Shinzato et al. 2014). The discrepancy between these studies could be explained by the different species used, which may possess different synthesis capabilities. However, Fitzgerald and Szmant (1997) acknowledge that the essential amino acids they found may be partially the result of biosynthesis by bacteria residing in the coelenteron (also known as the coelenteric cavity, gastrovascular cavity, or stomach)of the coral polyps. They ruled out that biosynthesis of the symbiotic zooxanthellae was responsible for the findings, as the pattern of radioactive amino acids detected was similar between the zooxanthellate (M. faveolata, A. cervicornis, P. divaricata) and azooxanthellate species (T. coccinea and A. poculata). What makes corals interesting and complicating animals is that they host symbiotic zooxanthellae, dinoflagellates with the ability to produce at least 14 amino acids, of which 7 are essential (Shinzato et al. 2014). The capability of coral-associated zooxanthellae to produce lysine and methionine is unclear, as some of the required enzyme-encoding genes were not found in their genome (Shinzato et al. 2014), although lysine synthesis was confirmed for the zooxanthellae of Aiptasia pulchella (Wang and Douglas 1999). Methionine may be produced by a combination of zooxanthellae and coral enzymes, which suggests that both symbiont partners have evolved to complement one another (Shinzato et al. 2014). Von Holt (1969) suggested something similar, as the zoanthid Zoanthus flos marinus (today known as Zoanthus sociatus) can produce glycine, unlike its zooxanthellae, possibly making the latter dependent on the zoanthid. Together, corals and their associated zooxanthellae can produce many amino acids (Acropora cervicornis in the waters off Curaçao, Dutch Caribbean. Image: Benjamin Mueller, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research). Tracer experiments with radioactive sodium carbonate (Na214CO3) have shown that zooxanthellae also transfer amino acids, or precursors thereof (glycoconjugates), to their host animal (von Holt and von Holt 1968; Markell and Trench 1993; Wang and Douglas 1999). Zooxanthellae convert the radioactive carbonate to amino acids via photosynthesis, after which the 14C-labeled amino acids are translocated to the host coral. This matches with genetic insights, which reveal that zooxanthellae have the necessary genes to produce transporter proteins for translocating amino acids to their coral host (Shinzato et al. 2014). All of this suggests that corals can acquire most, if not all amino acids via biosynthesis, either directly or via their symbiotic zooxanthellae and bacteria. It is also hypothesized that when corals feed on plankton, they gain additional nitrogen which allows the zooxanthellae to produce and translocate more amino acids to their coral host (Swanson and Hoegh-Guldberg 1998; Wang and Douglas 1999). Uptake from the external environment Next to producing amino acids via biosynthesis, corals can take up a range of amino acids from the seawater (Goreau 1971; Ferrier 1991; Fitzgerald and Szmant 1997; Grover et al. 2008). These include, but may not be limited to, histidine, leucine, methionine, valine, alanine, asparagine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glutamine, glycine and serine (Grover et al. 2008). Although the amino acid concentration of reef waters is very low (0.2-0.5 µmol L-1), corals have very efficient transport mechanisms to deal with this (Goreau et al. 1971; Grover et al. 2008). Transport proteins, also called carriers, present in the cell membranes of coral tissue (and all living organisms for that matter) allows corals to take up these scarcely available compounds. It has been found that amino acid uptake can be a significant source of nitrogen. For Stylophora pistillata, amino acids can account for 21% of the nitrogen uptake (Grover et al. 2008), although this will vary under different environmental conditions, i.e. the concentrations of ammonium, nitrate, urea and amino acids, and plankton abundance. For example, Grover et al. (2008) found that the amino acid uptake rate by S. pistillata increases 6-fold when the total amino acid concentration is artificially increased to 8 µmol L-1. For the corals S. pistillata and Galaxea fascicularis, and the zoanthid Zoanthus sociatus, amino acid uptake and incorporation into protein is higher in light than in darkness, whereas the opposite is true for Pocillopora damicornis (von Holt 1969; Al-Moghrabi et al. 1993; Hoegh-Guldberg and Williamson 1999; Grover et al. 2008). This suggests that photosynthesis plays a role in some species, possibly enhancing protein synthesis by the animal. This mechanism has been called light-enhanced amino acid assimilation (Al-Moghrabi et al. 1993). Normalized to biomass, amino acid uptake can be 5-7 times higher in the zooxanthellae compared to the host coral (Grover et al. 2008), although it is unclear why, as zooxanthellae are able to synthesize most amino acids themselves. The uptake by zooxanthellae is rapid, and occurs within two hours, possibly first via the seawater that fills the coelenteric cavity of coral polyps. This is plausible, as the zooxanthellae reside in the gastroderm which lines this cavity. Next to biosynthesis, corals and zoanthids can acquire amino acids from the seawater, in dissolved and particulate form (image: T. Wijgerde). Plankton also is an important source of amino acids, as bacteria, phytoplankton and zooplankton are all rich in protein. When corals feed on plankton, they can break down its proteins via digestion and liberate the amino acids. This digestive process is known as protein hydrolysis (breakdown of proteins using water), and is facilitated with enzymes known as proteases. In the same way, detrital matter can be a source of amino acids. When taking all sources together, we can see that corals can obtain all required amino acids, either via biosynthesis or uptake from the water in dissolved or particulate form. The question is, however, whether this amino acid supply is sufficient to maximise growth, i.e. whether it limits coral growth under natural conditions (see below). Overview of the two major amino acid sources for scleractinian corals; biosynthesis and uptake via the water column. Together, corals and zooxanthellae can synthesize 20 different amino acids, with some produced by the coral, others by the zooxanthellae, and yet others by both partners. It is important to note, however, that different coral species have different synthesis abilities. Amino acids can also be taken up via plankton, detritus and in dissolved form, which is known as heterotrophic feeding. The acquired amino acids are used by the coral to synthesize proteins for tissue growth, calcification and other processes (image: T. Wijgerde, based on Fitzgerald and Szmant 1997; Grover et al. 2008 and Shinzato et al. 2011, 2014). The role of amino acids in coral feeding and growth Feeding Similar to other animals, amino acids play important roles in the lives of corals, being essential to enzyme production, tissue growth and skeleton formation. In addition, amino acids are known to affect coral feeding behaviour. After the addition of frozen or live feeds to an aquarium, corals are often observed to extend their tentacles, a phenomenon which may be attributed to amino acids. Goreau et al. (1971) found that addition of the amino acids glycine, alanine or glutamate to the water resulted in opening of the mouth, tentacle extension, swelling of tissue and expulsion of digestive filaments for many scleractinian corals. Thus, these amino acids elicit the same feeding response as when zooplankton is supplied. It is possible that corals have receptors which recognize organic compounds, including amino acids. This ability to detect specific chemical compounds, known as chemotaxis, may allow coral polyps to recognize zooplankton and prepare for prey capture. Skeletal growth The important role of amino acids in the growth of living organisms is well-documented, and scleractinian corals are no exception. Not only do corals require amino acids to build protein for tissue growth, they also need these for synthesis of a so-called organic matrix (Allemand et al. 2004). This organic matrix is a framework of proteins, polysaccharides, glycosaminoglycans, lipids and chitin, and is essential to biomineralisation (Wainwright 1963; Young et al. 1971; Constanz and Weiner 1988; Falini 1996). In many corals, it forms a physical link between soft tissue and the skeleton, regulates and accelerates calcium carbonate deposition in the skeleton (calcification), and acts as "rebar", providing strength (Allemand et al. 2004). The building blocks of the organic matrix are secreted by coral cells into the skeleton, and this matrix is similar to that of animal bones and fish otoliths, and the cuticle of chicken eggshells. Organic matrices are also found in the skeletons of black corals (order Antipatharia) and hydrocorals (order Anthoathecata), the internal axis of gorgonians (order Alcyonacea), and the sclerites-needle-like calcium carbonate structures which provide strength-of soft corals (order Alcyonacea). The essential nature of an organic matrix for coral growth was demonstrated by Allemand et al. (1998), who were able to significantly reduce calcification of Stylophora pistillata by inhibiting organic matrix synthesis with specific drugs (emetin, cycloheximide and tunicamycin). Schematic overview of coral calcification. Energy is produced by calicoblastic cells, which line the coral skeleton at the underside of coral polyps. This energy is used to pump calcium ions into and protons out of a thin layer of fluid between the coral's tissue and skeleton, known as the calicoblastic fluid (CF). In addition, bicarbonate ions are transported to the CF, and generated in the CF from metabolically derived CO2 by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase (not shown). The high concentration of calcium and (bi)carbonate ions, together with a high pH, results in precipitation of calcium carbonate crystals around the organic matrix. This matrix regulates and accelerates calcium carbonate deposition, and acts as "rebar", providing strength. An essential component of the organic matrix is the amino acid aspartic acid (image: T. Wijgerde, based on Furla et al. 2000, Al-Horani et al. 2003a,b, Allemand et al. 2004 and Venn et al. 2011). Although its molecular composition is diverse, the protein component of the organic matrix in coral skeletons is dominated by the amino acid aspartic acid. In scleractinian corals, aspartic acid, glutamic acid and glycine make up a significant portion of organic matrix proteins, with aspartic acid accounting for up to 37% (Table 2). Aspartic acid is even more dominant in the spicules embedded in the internal axis of gorgonians, with up to 74.3% contributing to organic matrix proteins. For the hydrocoral Millepora alcicornis, a distant relative of true corals, we find a similarly high figure of 56.4%. Table 2. Amino acid composition of organic matrix proteins by percentage in three scleractinian corals (P. porites, A. palmata and A. fragilis), two gorgonians (E. tourneforti and Gorgonia sp.), and one hydrocoral (M. alcicornis). For all coral taxa, aspartic acid is the dominant amino acid. Based on Mitterer (1978). % of organic matrix proteins amino acid Porites porites Acropora palmata Agaricia fragilis Eunicea tourneforti Gorgonia sp. Millepora alcicornis aspartic acid 34.3 37.00 30.00 74.30 65.30 56.40 glutamic acid 10.00 12.50 10.30 3.86 5.78 11.00 threonine 2.09 3.09 2.54 1.29 0.63 4.41 serine 2.92 5.80 5.57 1.31 0.65 4.30 proline 3.54 3.83 3.96 1.05 1.26 1.88 cysteine 0.19 0.96 0.11 methionine 1.14 1.21 0.10 0.17 glycine 11.40 12.00 17.10 7.91 9.80 5.42 alanine 6.68 4.73 12.20 6.02 11.00 4.31 valine 5.58 4.57 5.56 1.36 1.74 2.30 isoleucine 4.60 2.18 2.38 0.51 0.94 1.67 leucine 6.87 4.36 4.50 0.59 1.35 2.23 tyrosine 0.99 0.80 0.78 0.12 0.12 phenylalanine 3.33 2.13 2.79 0.33 0.55 0.80 histidine 1.19 0.21 0.14 0.16 0.71 lysine 2.73 4.89 0.42 0.46 0.13 2.95 arginine 1.32 1.17 0.38 0.43 0.30 0.64 As the organic matrix of corals exhibits an abundance of aspartic acid, it stands to reason that its supply is critical to coral growth. Indeed, feeding scleractinian corals with daily batches of zooplankton (concentration range of 1,000-13,000 prey L-1 seawater) has been found to enhance tissue and skeletal growth, which may be partly caused by increased supply of aspartic acid and other amino acids, enhancing organic matrix synthesis and thus calcium carbonate deposition (Lavorano et al. 2008; Houlbrèque and Ferrier-Pagès 2009; Osinga et al. 2011). As providing scleractinian corals with higher than natural food quantities results in increased growth rates, coral growth on reefs is likely limited by food availability, and coupled to that the supply of amino acids, lipids and other organic compounds. In the same way, corals growing in deep waters or low flow areas can be naturally growth-limited by light availability and water flow rate (Wijgerde and Tilstra 2014 and references therein). Organic matrices are found in the skeletal components of all corals, including gorgonians (left), hydrocorals (Distichopora sp., upper middle), black corals (Cirrhipathes sp., upper right), scleractinian corals (Cycloseris sp., lower right), and soft corals (Dendronephthya sp., lower middle, image: T. Wijgerde). Should concentrated amino acids be added to the aquarium? For aquarists, this is one of those Million Dollar Questions. The answer is not that straightforward, however. On the one hand, just as we humans do not require amino acids in fancy pills to stay healthy, so too can corals make do without amino acid supplements if they follow a natural diet. In the case of corals, a natural diet constitutes regular feedings with live or frozen zooplankton (<10 prey L-1 seawater) and phytoplankton (~1,000,000 cells L-1 seawater), depending on species (Yahel et al. 1998; Heidelberg et al. 2004, 2010; Holzman et al. 2005; Yahel et al. 2005a,b; Palardy et al. 2006). On the other hand, although corals can grow under low amino acid concentrations and only small amounts of zooplankton, they are likely growth-limited under such a natural food availability. Thus, providing corals with higher than natural food quantities can increase growth rates (Lavorano et al. 2008), although this is not always the case (Forsman et al. 2011). In this respect, dosing concentrated amino acids may enhance coral growth, in the same way as batch feeding with zooplankton can do this. This theory is supported by the findings of Grover et al. (2008), who found that amino acid uptake by corals can be enhanced by artificially increasing the amino acid concentration. If an aquarium is heavily stocked with corals, it can be especially useful to feed copious amounts of plankton or dose concentrated amino acids on a daily basis, to compensate for the high grazing pressure. As they usually are well-stocked with fish, most home aquaria receive a significant amount of amino acids via artificial feeds (image: T. Wijgerde). Despite our scientific knowledge on amino acids and corals, there are no studies that show how dosing concentrated amino acids affects corals. In this perspective, there seems to be uncharted territory for both aquarists and scientists, who can test the effects of concentrated amino acids on coral growth and coloration. Aspartic acid is an interesting candidate to start with, given its important role in organic matrix synthesis and skeletal growth. It is possible that corals which receive a concentrated aspartic acid supplement on a daily basis show faster growth compared to corals fed with zooplankton (which may provide less aspartic acid). The outcome of such an experiment is determined by whether corals fed with zooplankton are growth-limited by their combined internal and external aspartic acid supply. When sufficient amino acids including aspartic acid are available in dissolved or particulate form, it may not matter what the source is. Thus, aquarists who already feed their corals heavily may not see an added effect of concentrated amino acids such as aspartic acid. For an experiment to have value, it is important to adhere to scientific standards, with sufficient replication and controls for solid conclusions. This means that one would have to use at least two separated aquaria to which amino acids are dosed, with several coral fragments in each aquarium, and at least two additional separate aquaria with fragments from the same parent colony receiving an alternative feed, or no feed at all, as controls to allow for comparison. In addition, all other environmental conditions, such as light intensity and spectrum, water flow rate, and water quality should be highly similar between the four aquaria to prevent confounding effects. Of course, it is possible that different species, and different genotypes (genetically distinct individuals) within species respond differently to concentrated amino acids (Osinga et al. 2011). Concluding remarks To conclude, it is fair to say that amino acids are highly important compounds for corals and other (marine) life. Whether you choose to supply your aquarium with amino acids via various feeds or in dissolved form is up to you. Either way, corals are highly adaptive creatures, and in many cases they will find a way to meet their minimum amino acid demand to stay alive and grow, either via biosynthesis or uptake from the water. References Al-Horani FA, Al-Moghrabi SM, de Beer D (2003a) The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar Biol 142:419-426 Al-Horani FA, Al-Moghrabi SM, de Beer D (2003b) Microsensor study of photosynthesis and calcification in the scleractinian coral, Galaxea fascicularis: active internal carbon cycle. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 288:1-15 Allemand D, Ferrier-Pagès C, Furla P, Houlbrèque F, Puverel S, Reynaud S, Tambutté É, Tambutté S, Zoccola D (2004) Biomineralisation in reef-building corals: from molecular mechanisms to environmental control. C R Palevol 3:453-467 Allemand D, Tambutté E, Girard JP, Jaubert J (1998) Organic matrix synthesis in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata: role in biomineralization and potential target of the organotin tribulyltin. J Exp Biol 201:2001-2009 Al-Moghrabi S, Allemand D, Jaubert J (1993) Valine uptake by the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis: characterization and effect of light and nutritional status. J Comp Physiol B 163:355-362 Constantz B, Weiner S (1988) Acidic macromolecules associated with the mineral phase of scleractinian coral skeletons. J Exp Zool 248:253-258 Falini G, Albeck S, Weiner S, Addadi L (1996) Control of aragonite or calcite polymorphism by mollusk shell macromolecules. Science 271:67-69 Ferrier MD (1991) Net uptake of dissolved free amino acids by four scleractinian corals. Coral Reefs 10:183-187 Fitzgerald LM, AM Szmant (1997) Biosynthesis of 'essential' amino acids by scleractinian corals. Biochem J 322:213-221 Forsman ZH, Kimokeo BK, Bird CE, Hunter CL, Toonen RJ (2011) Coral farming: effects of light, water motion and artificial foods. J Mar Biol Assoc UK, doi:10.1017/S0025315411001500 Furla P, Galgani I, Durand I, Allemand D (2000) Sources and mechanisms of inorganic carbon transport for coral calcification and photosynthesis. J Exp Biol 203:3445-3457 Fürst P, Stehle P (2004) What are the essential elements needed for the determination of amino acid requirements in humans? J Nutr 134:1558S-1565S Goreau TF, Goreau NI, Yonge CM (1971) Reef corals: autotrophs or heterotrophs? Biological Bulletin 141:247-260 Grover R, Maguer J-F, Allemand D, Ferrier-Pagès C (2008) Uptake of dissolved free amino acids (DFAA) by the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. J Exp Biol 211:860-865 Heidelberg KB, O'Neil KL, Bythell JC, Sebens KP (2010) Vertical distribution and diel patterns of zooplankton abundance and biomass at Conch Reef, Florida Keys (USA). J Plankt Res 32:75-91 Heidelberg KB, Sebens KP, Purcell JE (2004) Composition and sources of near reef zooplankton on a Jamaican forereef along with implications for coral feeding. Coral Reefs 23:263-276 Hoegh-Guldberg O, Williamson J (1999) Availability of two forms of dissolved nitrogen to the coral Pocillopora damicornis and its symbiotic zooxanthellae. Mar Biol 133:561-570 Holzman R, Reidenbach MA, Monismith SG, Koseff JR, Genin A (2005) Near-bottom depletion of zooplankton over a coral reef II: relationships with zooplankton swimming ability. Coral Reefs 24:87-94 Houlbrèque F, Ferrier-Pagès C (2009) Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol Rev Camb Philos 84:1-17 Markell DA, Trench RK (1993) Macromolecules exuded by symbiotic dinoflagellates in culture: amino acid and sugar composition. J Phycol 29:64-68 Mitterer RM (1978) Amino Acid Composition and Metal Binding Capability of the Skeletal Protein of Corals. Bull Mar Sci 28:173-180 Osinga R, Schutter M, Griffioen B, Wijffels RH, Verreth JAJ, Shafir S, Henard S, Taruffi M, Gili C, Lavorano S (2011) The biology and economics of coral growth. Mar Biotechnol 13:658-671 Palardy JE, Grottoli AG, Matthews KA (2006) Effect of naturally changing zooplankton concentrations on feeding rates of two coral species in the Eastern Pacific. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 331:99-107 Reeds PJ (2000) Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J Nutr 130:1835S-1840S Reimer J (2013). Zoanthus flos-marinus Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1860. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=590575 on 2014-02-11 Shinzato C, Inoue M, Kusakabe M (2014) A Snapshot of a Coral ''Holobiont'': A Transcriptome Assembly of the Scleractinian Coral, Porites, Captures a Wide Variety of Genes from Both the Host and Symbiotic Zooxanthellae. PLoS ONE 9(1): e85182. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085182 Shinzato C, Shoguchi E, Kawashima T, Hamada M, Hisata K, Tanaka M, Fujie M, Fujiwara M, Koyanagi R, Ikuta T, Fujiyama A, Miller DJ, Satoh N (2011) Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change, Nature 476:320-323 Srinivasan G, James CM, Krzycki JA (2002) Pyrrolysine Encoded by UAG in Archaea: Charging of a UAG-Decoding Specialized tRNA. Science 296:1459-1462 Swanson R, Hoegh-Guldberg O (1998) Amino acid synthesis in the symbiotic sea anemone Aiptasia pulchella. Mar Biol 131:83-93 Venn A, Tambutté E, Holcomb M, Allemand D, Tambutté S (2011) Live Tissue Imaging Shows Reef Corals Elevate pH under Their Calcifying Tissue Relative to Seawater. PLoS ONE 6(5): e20013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020013 von Holt C (1968) Uptake of glycine and release of nucleoside-polyphosphates by zooxanthellae. Comp Biochem Physiol 26:1071-1079 von Holt C, von Holt M (1968) Transfer of photosynthetic products from zooxanthellae to coelenterate hosts. Comp Biochem Physiol 24:73-81 Wainwright SA (1963) Skeletal organization in the coral, Pocillopora damicornis. Q J Microsc Sci 104:169-183 Wang JT, Douglas AE (1999) Essential amino acid synthesis and nitrogen recycling in an alga-invertebrate symbiosis. Mar Biol 135:219-222 Wijgerde T (2012) Aiptasia, dinoflagellate algae and cyanobacteria - a three-way symbiosis? Advanced Aquarist 11(4) Wijgerde T, Tilstra A (2014) Debunking Aquarium Myths. Advanced Aquarist 13(2) Yahel G, Post AF, Fabricius K, Marie D, Vaulot D, Genin A (1998) Phytoplankton distribution and grazing near coral reefs. Limnol Oceanogr 43:551-563 Yahel R, Yahel G, Berman T, Jaffe JS, Genin A (2005a) Diel pattern with abrupt crepuscular changes of zooplankton over a coral reef. Limnol Oceanogr 50:930-944 Yahel R, Yahel G, Genin A (2005b) Near- bottom depletion of zooplankton over coral reefs: I: diurnal dynamics and size distribution. Coral Reefs 24:75-85 Young SD, O'Connor JD, Muscatine L (1971) Organic material from scleractinian coral skeletons. II. Incorporation of 14C into protein, chitin and lipid. Comp Biochem Physiol 40B:945-958 View the full article

-

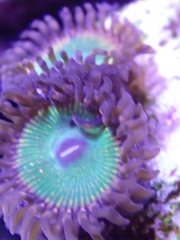

Click through to see the images. These are time-lapse photography captured by youtube user ozguncyprus. The first video shows a bubble coral inflating from from its skeleton into the recognizable appearance that gives it its namesake. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> An amazing Ricordea sp. does a mesmerizing throbbing dance as it rises to life. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> It's difficult to appreciate zoanthids "blooming" in real time, but time-lapse really brings the process to life. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> Another zoanthid "flowering" for good measure: " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> A finger leather takes on its tree-like form. " height="383" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="680"> "> "> View the full article

-

Mix bed resin can mean other media as well. Sent from my GT-I9300 using Tapatalk 2

-

Click through to see the images. Credit: Thomas Pohl Reef Life Finds A Way Iraq is almost entirely landlocked except for a narrow stretch of land bordering the Persian Gulf where the Shatt al-Arab river exits into the sea. Previously, scientists did not believe corals could exist there because its conditions are extremely inhospitable for corals. The river causes drastic fluctuations in temperatures (57-93°F, 14-34°C), rapidly shifting salinity, and very high turbidity due to sediment and sometimes even crude oil runoff from the river. "Not ideal for coral growth" is an understatement. Yet, corals grow here and not just a handful of species. The dive team identified multiple photosynthetic stony corals including Platygyra pini, Turbinaria stellata, Porites lobata, Porites sp., and Goniastrea edwardsi. They also discovered azooxanthellate stony corals Astroides calycularis and Tubastrea sp. as well as a number of octocorals (e.g. soft corals and gorgonians) such as Junceella juncea and Menella sp. Amongst these corals lived other reef organisms like brittle stars. The unexpected discovery was first made in September 2012 with subsequent surveys identifying more corals. Their findings was published this month in Nature's Scientific Report. This reef may not look like much, but the fact that it exists in such a hostile environment is amazing in and of itself. Credit: Thomas Pohl Credit: Thomas Pohl " height="380" style="float: left; " type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="670"> "> "> View the full article

-

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

The piping for the water change and drainage. Notice there is two valve which allow me to switch between the water change drain mode and new salt mix fill up mode. -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

The outdoor fiber glass 6 x 3 x 3 feet mixing tank which will be connected to the main tank inside the fish room. Still waiting for the lip cover to come .... -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

Caribsea mineral muds for the refugium tank -

1000 Gallon 3D Hole in the wall

Harlequinmania replied to Harlequinmania's topic in Members Tank & Specs

Finish filling up Rack A and started tank cycling with all the filter media